What’s on the top of your mind?

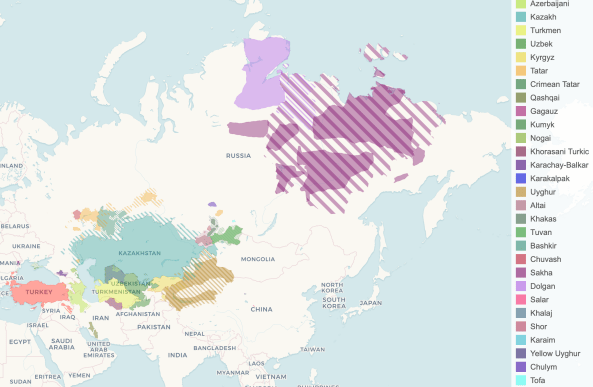

Would you fancy your look with a tübәtәi, kalfaq or büreq? These and several other bashlyqlar are the types of Tatar headwear that are an integral part of the traditional Tatar image, identity, and costume. Covering the head became especially significant for the Tatars from the time their forefathers and foremothers (the Volga Bulgars) accepted Islam in 922 CE: It gained religious and mental importance. In Islam, wearing a headcover symbolizes humility, modesty and respect to the Creator. It signals care about community. It indicates openness and desire to seek knowledge.

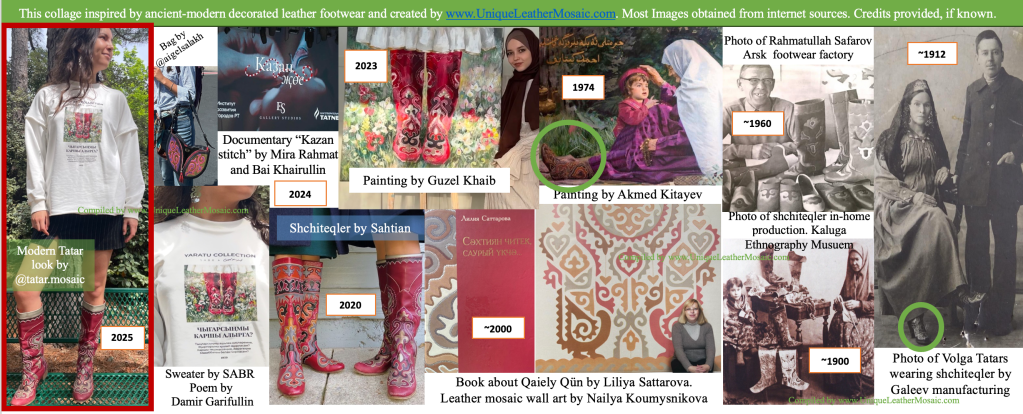

Our own unwavering curiosity in discovering new dimensions and applications of unique leather art of the Tatars has led us to a digital collection of Nordiska Museum of Sweden. The museum owns a hat that, unexpectedly, features 3 integral elements of the unique Kaiyly Kün technology that are typically a feature of traditional Tatar footwear, shchiteqler.

This one-of-a-kind leather hat had been created with 1) colorful soft leather cutouts, 2) stacked to create stylized Turkic-inspired design, and 3) manually attached with distinctive inward stitching. This unprecedented example of the headwear decorated with Kaiyly Kün technology is only the second kind that we have ever encountered (Read about our first discovery in digital collection of National Museum of Finland here).

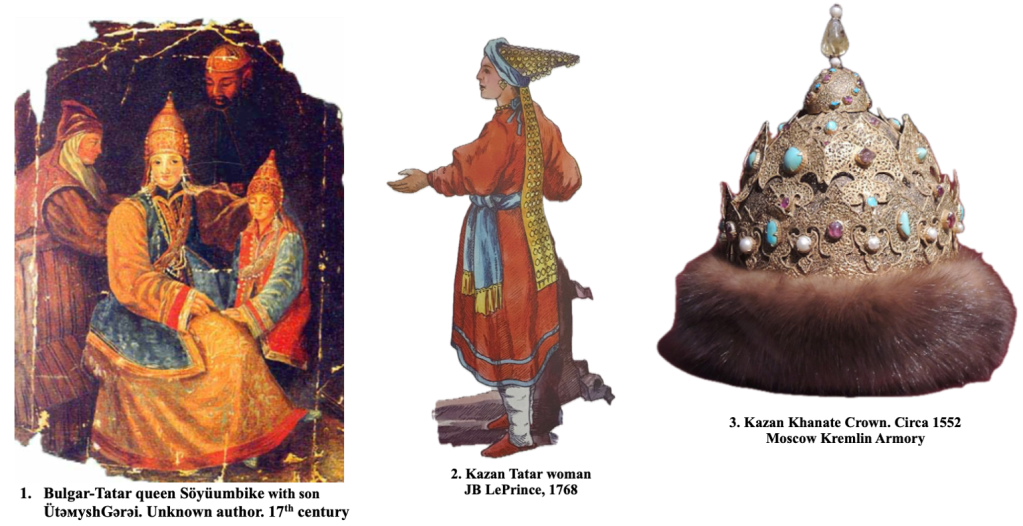

We took a liberty of improvisation, and imagined how this unique colorful leather hat would accentuate a Tatar Muslim woman’s look. Although this type of elongated headwear is not in the Tatar fashion anymore, it does bring forward three historic imagery: 1) iconic depiction of Bulgar-Tatar queen Söyüumbike (1513-1553) by unknown author of 17th century, 2) intriguing drawing of Kazan Tatar woman by Jean Baptist Le Prince (1734-1781), and, 3) the Crown of Kazan Khanate (1438-1552) that was submitted to Ivan IV of Muscovite Tsardom in 1552, and it is now resting in Moskva Kremlin Armory of Rossiyan Federation.

Writing this post during Ramadan, the month when Holy Qur’an was revealed to Prophet Muhhamad by Angel Jibrael in Makkah, reminds us of the very first word قرأ / Iqra / Read that opens the Surah Al’ Alaq that is believed to be the first revelation. It starts with the command to “Read in the name of the Lord who created…” (Qur’an 96:1). It channels undeniable truth of power of learning. It calls for acquiring knowledge that illuminates, inspires, awakens the heart. In the times of reign of Artificial Intelligence and social media, it is paramount to invest time and efforts in continuous learning, meaningful discoveries and support of learning communities.

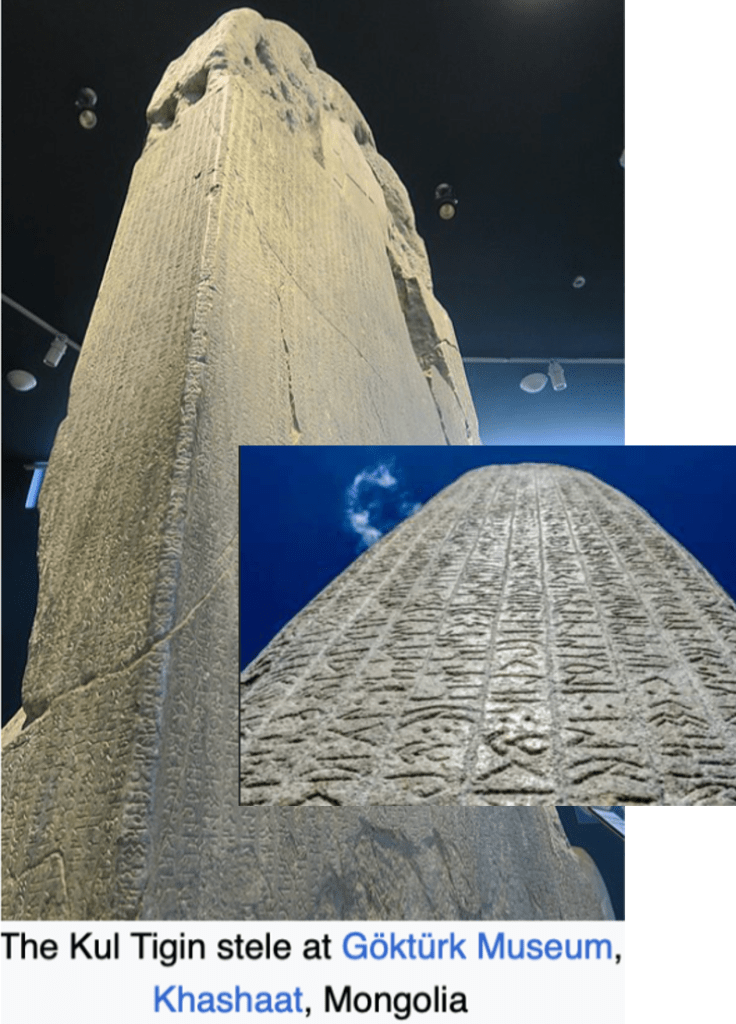

Start here by learning about curiously complex history of the Tatars.

Start here by supporting and donating to the only Tatar online school that teaches Tatar language, literature, history globally.

The Tatar language is one of many stateless languages that face existential threat: It is critical to keep ethnic languages thriving, so the world is open-minded, tolerant and appreciative of a diverse thought.

That’s what’s on the top of our mind!

Wait!…Here is one more, the freshest discovery quietly tucked in the small city of Taos, State of New Mexico, the US. This wood-carved girl wrapped in a yawlyk with kalfaq on her head is the work of Nikolai Feshin (1881-1955), a famous painter born and raised in Kazan in late 19th-early 20ies centuries, who moved to the USA in 1933.

Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan Republic, is and has been a unique place of co-existance of Muslim, Christian, pagan, Turkic, Slavic and Finno-Ugric population in Rossiyan Empire, USSR, Rossiyan Federation. This unique conglomerate of diversity of cultural cues influenced Feshin’s art and his interest in depicting the native people of the lands, both of Tatarstan and of then Mexico-now-USA. This one-of-a-kind carving of Tatar/Turkic girl is housed in the Taos Art Gallery that is in the house designed, built and carved by multi-talented Nikolai Feshin himself.

Sources:

- Leather hat (NM0011102) decorated with Kaiyly Kün technology from Digital Museum Nordiska Museet Collection

- Drawing of female by Kh.Betretdinova, 2010 for Postal Service of Rossiyan Federation

- Tatar Costume, M. Zavyalova, 1996

- Tatar Halyq Kiemnyare, Ramziya Mohamedova, 1997

- Qur’an

- Taos Art Gallery at Fechin House, Taos, New Mexico, USA