The day of December 15th has recently been proclaimed by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) as a World Turkic Language Family Day. In 2025, we are celebrating it for the first time!

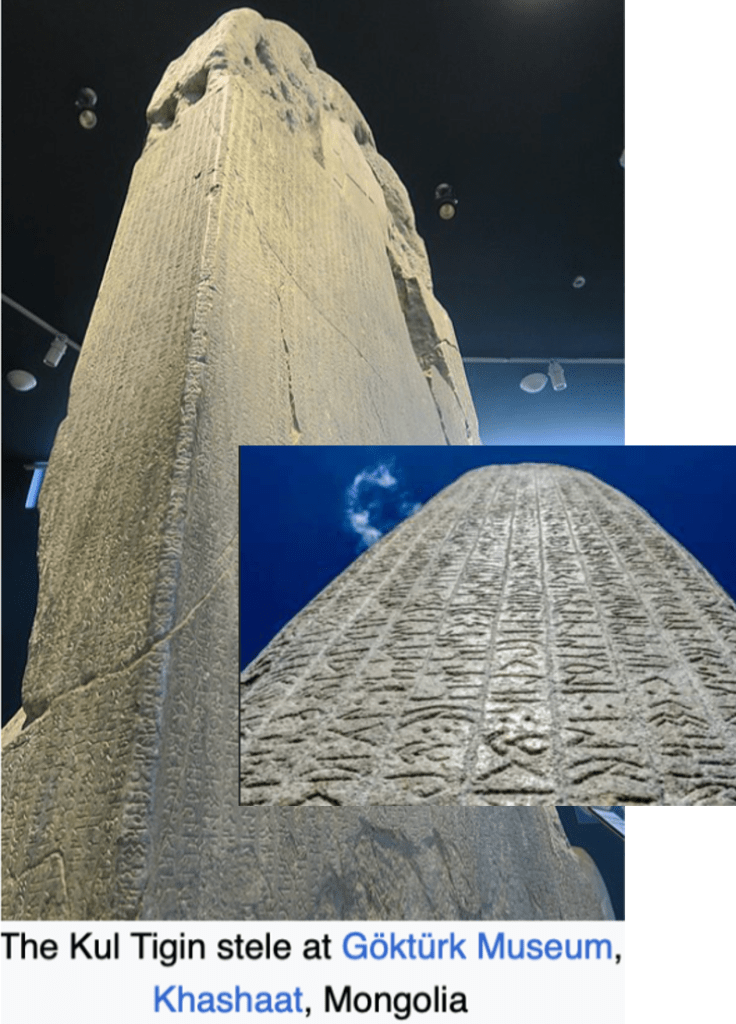

On this day in 1893 a linguist and turkologist Vilhelm Thomsen (1842-1927) made a very anticipated announcement that the text of the Orkhon Inscriptions (discovered in 1889 during the expedition of Nikolai Yadrintsev (1842-1894)) was deciphered (translation here). The 1300 years old inscriptions, also referred as Kul Tigin (684-731) steles and Bilge Qaghan (683-734) inscriptions, found in Orkhon valley of modern Mongolia, are the oldest known written records of the Turkic language.

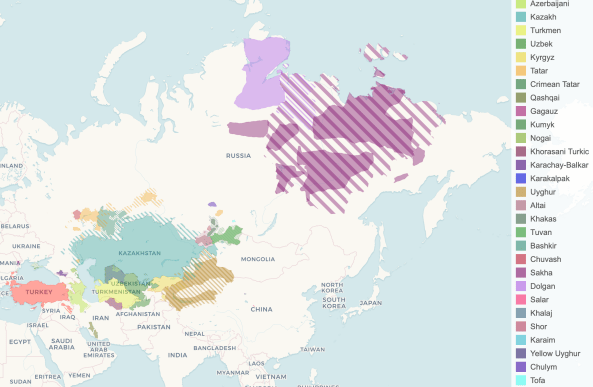

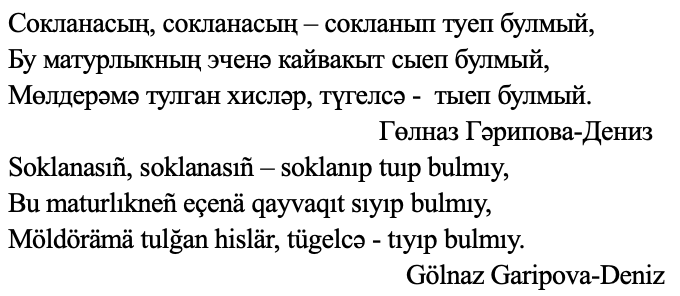

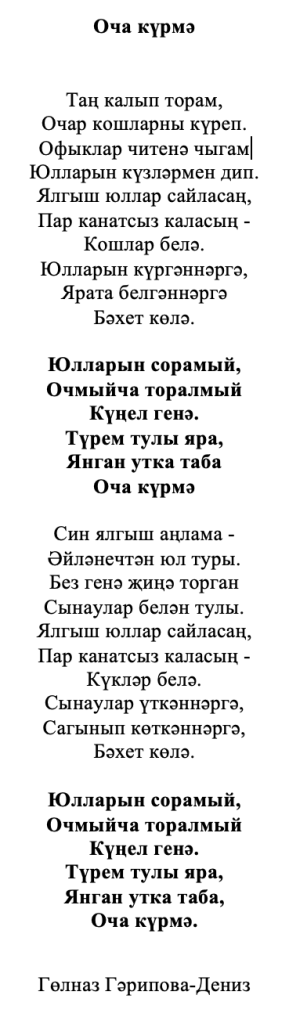

Out of ~8 billion people worldwide, roughly 200 million are speaking Turkic languages, ~7 millions of whom are the Tatar language speakers/ carriers, active and passive. Although the usage of the Tatar language is diminishing due to the prevalence of various lingua franca in the areas of modern habitats, there is a great interest in learning and preserving the Tatar language these days, simply because it connects to the roots (incredibly rich oral, written, material heritage) and to the other Turkic people.

Turkic languages are characterized by the vowel harmony and agglutinative nature of grammatical relations between the words. According to the lexicostatistical matrix of Turkic languages and the article in Journal of Language Evolution, the Tatar language exhibits more than 50% of basic lexical similarities with most of the Turkic languages including Azerbaijani, Bashkir, Gagauz, Kazakh, Karakalpaq, Karachi, Khakas, KirimTatar, Turkish, Turkmen, Tuvan, Uyghur, Uzbek. To have an idea how closely they sound, just give a listen to Bulat Shaymi’s short song where he sings in 12 Turkic languages!

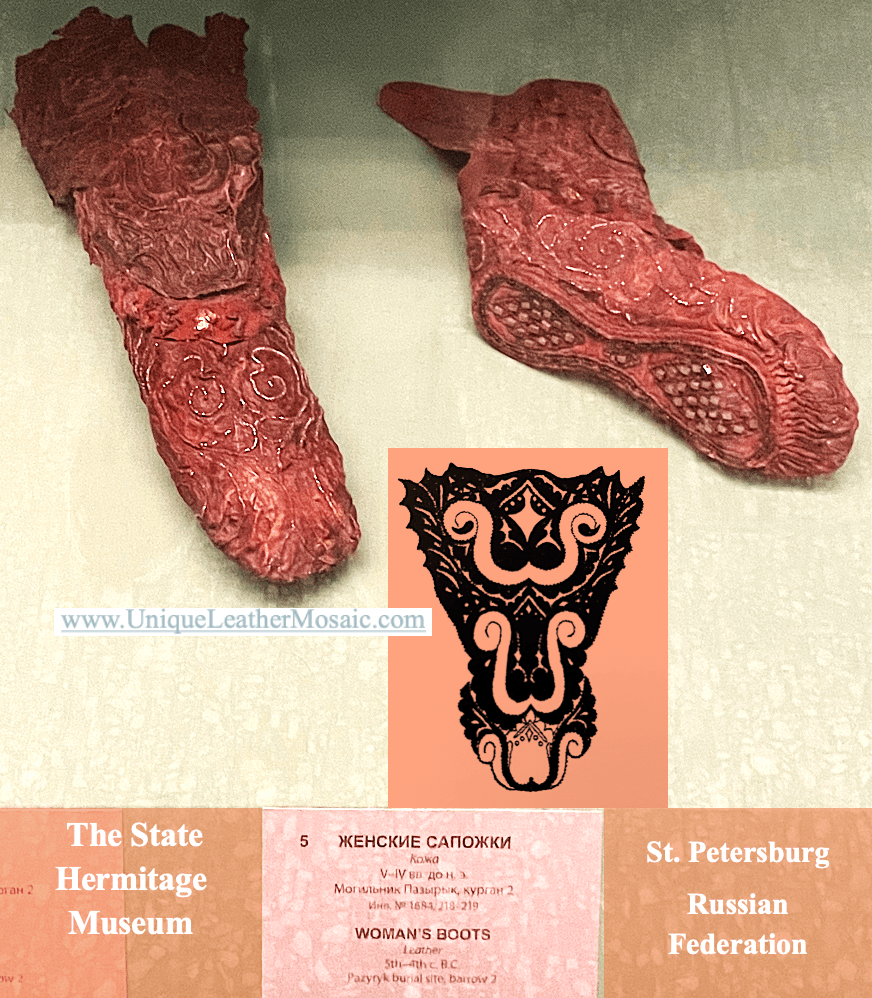

For several millennia, in the vast territories of central EuroAsia, impressive networks have been connecting, non-stop, the flow of goods, skills, thoughts through the well-established trading routes (Volga Route powered by the Volga Bulgars, ancestors of the modern Tatars, and Silk Road) that had been managed by various influential forces, including nomadic Saka/ Scythian Empire, Turkic Kaganates, Mongol Empire evolved into several Turkicized khanates later become referred as Turkistan (Turan by Persian sources, Transoxania, Central Asia by western sources) -the ethnonym represents a conglomerate of many Turkic-speaking states/“-stan”s-, Rossiyan Empire through 1917.

Although Tatarstan is not a part of Turkestan geographically, the linguistic, customary and historic baseline of the Tatars (originally, Volga Bulgars) of the Volga-Ural area of modern Rossiyan Federation is linked to all Turkic people. The intelligible wide-spread Turkic languages have eased up the channels to carry on business, policies, thoughts, innovations, and the Tatars were instrumental in promoting successful collaborations and opportunities for the Turkic languages-speaking world and its neighbours creating so-called Tatar Empire, a term coined by Danielle Ross in her book.

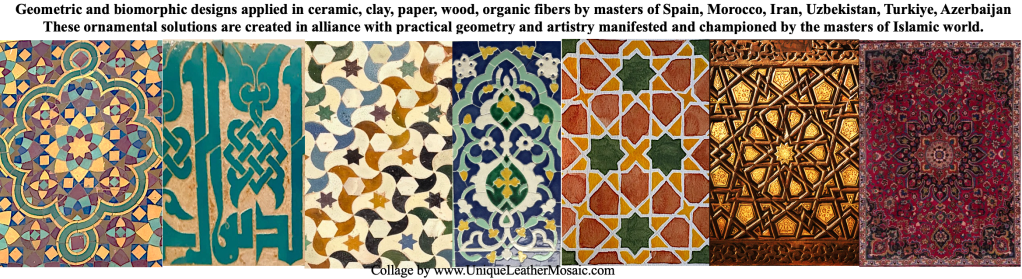

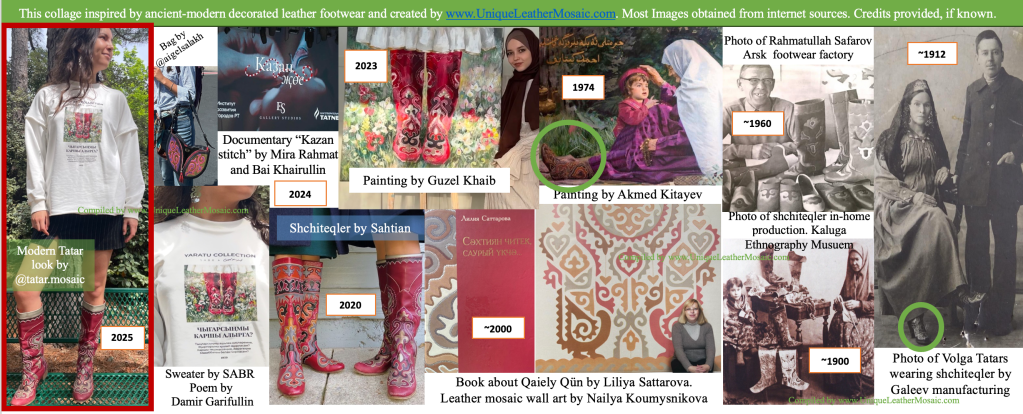

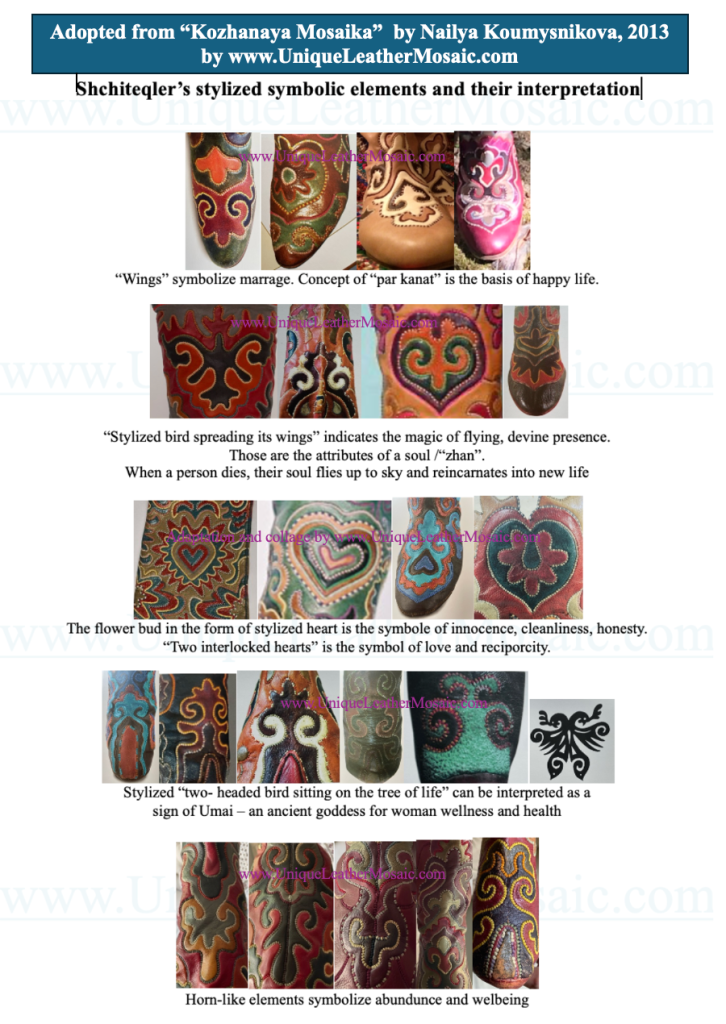

Material cultures of the Turkic people have many common features that speak to the unified sources of inspirations and beliefs (a subject for a separate post), the distribution of which showcases the collaborative nature of the networks. The simple fact that shchiteqler – boots uniquely decorated with Kaiyly Kün technology mastered by the Volga Tatars – exhibited in collections of many museums worldwide and labeled as originated from various Turkic-speaking places (such as Asia, China, Crimea, East & West Turkestan, Europe, Georgia, Indonesia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Tatarstan, Russia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan) speaks volumes.

The above Images of shchiteqler are courtesy of online collections (linked further) of PennMuseum of University of Pennsylvania, USA, Museum of Ethnography of Hungary, Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, USA, Metropolitan Museum of Art, USA, Ethnography Museum of Sweden, British Museum of Great Britain.

The due credit and appreciation are not always given to the skilful developers of the unique art in those museum collections: Successful Tatar leather artisans and entrepreneurs had not only manufactured uniquely decorated footwear in its “birthplace” Kazan-Arshcha area of Tatarstan to sell globally, but also had travelled far to trade and open workshops in Central Asia/Turkestan, Caucasus, Eastern Europe, cities of Rossiyan Empire. They shared their exceptionally-processed leather technology inherited from the Volga Bulgars (referred as bulgari/ safiyan/ sahtiyan/ yuft’) and unique decorated footwear making skills, they trained apprentices throughout European and Asian continent for centuries up until early 20ies century.

Let’s celebrate, promote and practice the

Arts of Native “Skilled Tongues” and “Skilled Hands” everyday!